Hemoglobinuria – Silent Red Flags You Need To Recognize

Hemoglobinuria can remain unnoticed for a long time, as its early signals often seem insignificant. Recognizing changes in urine, unusual fatigue, or other subtle symptoms in time can help prevent serious complications. Learn which “red flags” you should never ignore to better protect your health.

Hemoglobinuria is not the same as simply “seeing blood” in the urine. It refers to hemoglobin (the oxygen-carrying protein inside red blood cells) passing into urine after red blood cells break apart in the bloodstream. Because the color change can be subtle and intermittent, recognizing the pattern and related symptoms can help you describe what’s happening clearly during a medical visit.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.

Causes of hemoglobinuria and red blood cell breakdown

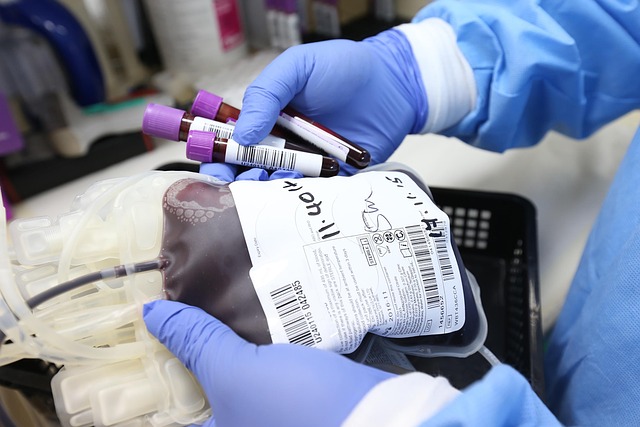

Hemoglobinuria most often reflects intravascular hemolysis, meaning red blood cells are being destroyed within blood vessels rather than being removed normally by the spleen. Triggers range from inherited blood disorders to acquired immune problems. Examples include hemolytic anemias, severe infections, transfusion reactions, certain toxins, and mechanical destruction of red blood cells (for example, from some types of heart valve disease). A rare but important cause is paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), in which abnormal blood cells are unusually vulnerable to complement-mediated destruction.

Recognizing context matters. Dark urine that appears after strenuous exercise, following a new medication, or during a febrile illness can provide clues. Associated symptoms may include unusual fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness, rapid heart rate, jaundice (yellowing of the eyes or skin), or back/abdominal pain. Because these symptoms overlap with other conditions, lab testing is usually required to confirm the cause.

How hemoglobinuria is diagnosed through lab testing

Clinicians typically start with a urinalysis. A urine dipstick may show “blood” because it detects heme, but microscopy may reveal few or no intact red blood cells—an important pattern that supports hemoglobinuria rather than hematuria. Additional urine findings can include protein or casts depending on how the kidneys are affected.

Blood tests help confirm hemolysis and narrow down the cause. Common labs include a complete blood count (to assess anemia), reticulocyte count (bone marrow response), lactate dehydrogenase (often elevated in hemolysis), haptoglobin (often low because it binds free hemoglobin), and bilirubin levels. A peripheral blood smear can suggest certain diagnoses by showing abnormal cell shapes. If PNH is suspected, flow cytometry testing for specific surface markers on blood cells is often used to support the diagnosis. Test selection and interpretation depend on the full clinical picture.

Risks and complications linked to untreated hemoglobinuria

Hemoglobinuria is a sign, not a diagnosis, but it can signal conditions that carry real risks if left unaddressed. Significant hemolysis can lead to anemia severe enough to reduce oxygen delivery to tissues, contributing to weakness, chest discomfort in vulnerable individuals, or reduced exercise tolerance. Ongoing hemolysis can also increase bilirubin and contribute to jaundice or gallstone formation over time.

The kidneys are another major concern. Free hemoglobin can be harmful to kidney tubules, and repeated or severe episodes may contribute to acute kidney injury, especially with dehydration or other stressors. Some underlying causes—such as PNH—can also be associated with blood clots in unusual locations, which is a medical emergency. Because the complication profile depends heavily on the underlying condition, persistent or recurrent dark urine should be evaluated rather than watched passively.

Differences between hematuria and hemoglobinuria

Although both can change urine color, hematuria and hemoglobinuria come from different processes. Hematuria means intact red blood cells are present in the urine, usually from bleeding somewhere along the urinary tract (kidneys, ureters, bladder, prostate, or urethra). Common causes include urinary tract infections, kidney stones, enlarged prostate, vigorous exercise, or—less commonly—tumors.

Hemoglobinuria, by contrast, usually reflects red blood cell destruction in the bloodstream with hemoglobin filtering into urine. The distinction affects what tests come next. With hematuria, clinicians often focus on imaging and urologic evaluation if indicated; with hemoglobinuria, the workup often centers on hemolysis labs and hematology considerations. A practical “red flag” detail to share is whether urine testing showed heme on dipstick but little to no red blood cells under the microscope, which points away from classic hematuria.

Living with chronic hemolytic conditions

For people who have an ongoing hemolytic disorder, daily management often focuses on monitoring, preventing triggers, and reducing downstream complications. The exact plan varies widely—someone with an inherited condition may need a different approach than someone with an acquired immune-mediated anemia or PNH. Regular follow-up may include tracking hemoglobin levels, markers of hemolysis, kidney function, and iron status. Symptoms such as increasing fatigue, new shortness of breath, or recurring dark urine episodes are often used to decide when reassessment is needed.

Supportive strategies are typically individualized and clinician-guided, but may include hydration planning during illness, reviewing medications and supplements for potential triggers, and keeping a record of episodes (timing, urine color changes, associated pain, fevers, or exertion). If PNH is diagnosed, treatment discussions may include therapies aimed at reducing complement-driven hemolysis and careful evaluation of clot risk, balanced against side effects and monitoring needs. Because chronic hemolysis can affect multiple organ systems, coordinated care between primary care and specialists is common.

Hemoglobinuria can be easy to dismiss as a temporary urine color change, but it often reflects an underlying process that deserves attention. Noticing patterns—such as recurrent dark urine, symptoms of anemia or jaundice, or lab findings consistent with hemolysis—can help clinicians distinguish hemoglobinuria from hematuria and identify the next steps. When the cause is found, management usually focuses on treating the underlying condition and monitoring for complications, especially anemia, kidney stress, and clot-related risks in select disorders.